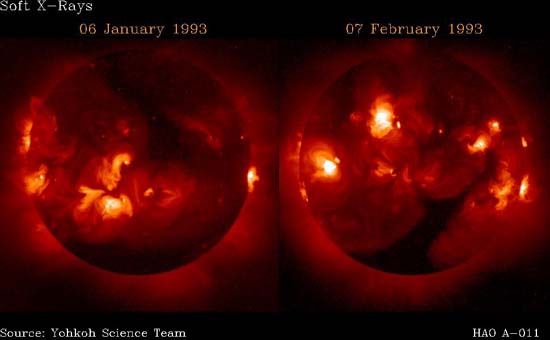

11. The Sun in X-rays

With a surface temperature of 5800 K, the Sun should normally emit

no X-rays at all, and so should look completely dark on an X-ray image.

Experience reveals that this is not the case, as demonstrated first

by X-ray telescopes onboard the Skylab space station, and

exemplified here

by two X-ray images of the Sun taken on different days with an X-ray

telescope on board the Japanese satellite Yohkoh. While large

portions are indeed dark, small, very bright regions are also quite

conspicuous. X-ray bright regions indicate heating to temperatures

in excess of 2 million degrees Kelvin. Comparisons of such images

with, for example, white

light images (see slide #1) taken simultaneously reveal that the

brightest

X-ray emitting regions are almost always overlying sunspots or active

regions. Sequences

of X-ray images occasionally reveals very sudden and short lived

increases in brightness, known as flares.

During such events, the X-ray brightness

of a flaring active region often exceeds the total X-ray brightness

of the rest of the Sun. Flares are also visible

as brightening in H![]() , and

sometimes even in white light.

They are one of the manifestations of the class of phenomena

grouped under the heading of solar activity.

The reconfiguration and dissipation of magnetic fields via

reconnection

is believed to be the energy source of solar flares.

Other noteworthy features on these images are the very dark regions

located near the south solar pole, called

coronal holes. Coronal holes are usually located above the

solar poles, but sometimes may extend down to lower latitudes, as

illustrated by these two images.

, and

sometimes even in white light.

They are one of the manifestations of the class of phenomena

grouped under the heading of solar activity.

The reconfiguration and dissipation of magnetic fields via

reconnection

is believed to be the energy source of solar flares.

Other noteworthy features on these images are the very dark regions

located near the south solar pole, called

coronal holes. Coronal holes are usually located above the

solar poles, but sometimes may extend down to lower latitudes, as

illustrated by these two images.